Presentation :

Pourquoi pas autrement ?

La galerie existe depuis 2011, mais entre Emmanuel Hervé et Charles-Henri Monvert, il y a dix-sept années de complicité. Or si elle explique pas mal de chose, cette relation n?entame rien à la particularité de voir les tableaux du second chez un marchand de trente ans son cadet.

Pour la deuxième exposition de Monvert chez Emmanuel Hervé, trois tableaux sont réunis. La taille de la galerie n?en supporterait pas beaucoup plus, et c?est très bien ainsi. Alors, comment ces ?uvres ont-elles été choisies ? J?ai posé la question à l?artiste et au galeriste. Comme ils étaient tous deux réunis ce soir-là, et comme Emmanuel ne semblait pas vouloir ou pouvoir répondre, je constatai qu?il m?interpellait du coin de l??il quand, l?autre demeurant aussi silencieux, pour avancer, je lui demandai directement comment et pourquoi il les avait peints ? La réponse fusa : « C?est sorti comme ça. Ça s?est imposé. » Mes questions étaient difficiles, évidemment, et sans doute un tantinet empesées, mais en deux pentasyllabes, l?affaire était expédiée. Je n?en étais pas plus avancé, mais je compris rétrospectivement le regard oblique du muet supporter. La complicité, ça se passe (aussi) de commentaire, mais ça s?entretient avec des mimiques. Comme il n?y avait aucune désinvolture dans la déclaration de l?artiste, il n?y avait aucun dépit dans le second coup d??il que je reçus aussitôt, plutôt une espèce de soulagement, peut-être même l?expression d?une profonde félicité, un acquiescement sans réserve au moins. Comprendre :

_ Premièrement : Monvert ne fait pas de la peinture, il fait des tableaux.

_ Deuxièmement : le tableau échappe à tout contrôle.

Le premier postulat n?est pas si absurde qu?il y paraît d?abord. Car si pour faire un tableau, il n?est pas interdit de le peindre, on sait qu?on peut s?y prendre autrement et d?ailleurs de plus en plus d?artistes s?évertue à ne pas se salir les mains. Or Monvert peint bel et bien le tableau qu?il fait, et du matin au soir il passe même son temps à ça. Mais s?il n?insiste pas sur l?étape nécessaire de l?exécution (qu?il faut bien dépasser pour arriver quelque part), sur l?ascétique discipline de l?atelier (où il ne convie personne, pas même son marchand), c?est parce que le tableau fait ? s?entend : celui considéré comme achevé ? doit effacer sa besogneuse genèse, sinon toutes ses traces, pour s?offrir comme un phénomène n?ayant au fond rien à voir avec ce qui a précédé. Pas quelque chose de franchement nouveau, mais quelque chose d?absolument neuf. Comme si, en complète conformité avec les clichés de l?abstraction, le domaine de l?art n?était accessible que dans un état second, sous l?effet de certaines stimulations étrangères au réel. Ce que vient d?ailleurs contredire le récolement de coupures de presse auquel se livrent les proches de l?artiste, à commencer par son marchand, depuis qu?un de ses tableaux acquis par le Fonds national d?art contemporain (FNAC) a été accroché dans le bureau princier d?une haute administration et qu?il apparaît à l?arrière plan d?interviews donnés par les différents ministres se succédant à ce poste et lui tenant compagnie en lui tournant le dos ? encore que preuve est ainsi faite que l?art peut se manifester jusque dans le bureau d?un ministre : les risques de distraction demeurant tout de même limités pour ses interlocuteurs face à un tableau abstrait ; mais qui, en audience solennelle, n?a pas laissé s?égarer son regard vers un détail anodin : un crayon dans le pot à crayons, l?ombre d?un radiateur ou une tache de boue à la pointe d?un soulier ?

Le second postulat est lié au précédent, on le comprend assez bien.

Pour que l?auteur d?un tableau, premier intéressé, soit devant lui plongé dans l?état « cataleptique » recherché : celui qui lui fait dire qu?il y a bien un tableau sous ses yeux, que celui-ci tient debout, qu?il fonctionne, comme une lampe s?allume quand on actionne l?interrupteur ? et même un peu mieux ?, il faut que son exécutant ait tout oublié de la manière dont il s?y est pris pour en arriver là : techniquement, mais surtout en amont de toute technique. Quelles étaient ses intentions en s?y mettant ? etc. Or c?est la question que j?avais posée à Monvert et on sait où elle nous a menés !

Car l?artiste écarte toute idée de projet, de contrôle, d?intervention même, de protocole en tout cas, au profit de cette autonomie fantasmatique du tableau comme objet, dont on nous a déjà rebattu les oreilles, mais rarement de façon aussi désopilante .

Si dans un joyeux désordre on cite devant lui Knoebel, Molnar voire LeWitt, Monvert laisse dire avec placidité. Mais il faut citer Martin Barré pour qu?il s?exalte, et Brice Marden, pour l?entendre réfuter énergiquement.

La grille qu?il trace sur la toile à la mine de plomb et qui transparaît encore ça et là n?est pas un principe directeur, c?est un échafaudage qui aide à composer ou à s?évader de la composition préconçue. En tout cas elle n?a rien à voir avec la grille minimaliste. L?échafaudage peut rester à demi accroché à l?ouvrage. La grille américaine est all over. Ce qui les oppose.

Les tableaux de Monvert sont plutôt lisses. Pourtant, selon l?artiste, tout se passe dans la matière picturale bien plus que dans la composition ou dans la couleur. La faible épaisseur qui donne à la matière cette consistance procure sa tension et l?intensité chromatique voulue (?) au tableau. L?« intensité chromatique » considérée comme consistance propre de la peinture-phénomène, donc indépendamment de la relation des couleurs entre elles. ? Pas mal pour un peintre abstrait dont le patronyme fait copuler, avec un pronom possessif, la couleur aux infinies nuances que s?interdisait Mondrian ! Mon-vert vous dira par exemple que telle bande était jaune, qu?il aurait aussi bien pu utiliser une autre couleur, et qu?elle est devenue noire ? qui est ou n?est pas une couleur, selon les points de vue, ma mère me le demandait encore récemment, mais passons ! ?, non parce que ça n?allait pas, mais pas parce que le noir est forcément plus satisfaisant, parce qu?il s?imposait.

Comme si l?ordre était venu d?en haut.

Comme si cette injonction à faire rejetait d?office dans un passé antédiluvien l?expérience de la production du tableau.

Comme si l?artiste était frappé d?amnésie et même d?empêchement à « refaire » le tableau, c?est à dire à en retracer le scénario, à supputer son archéologie ; plus démuni, en somme, que quiconque devant sa propre production, parce que n?importe quel autre observateur un tant soit peu curieux adopte cette démarche rétrospective devant une ?uvre qui l?intéresse.

Comme si ? pardon si je me répète, le trouble de Monvert doit être communicatif ?, comme si ce n?était pas le même tableau qui faisait l?objet des deux expériences, celle de l?exécution et celle de la scrutation une fois la précédente révolue, une fois le fil du temps tranché pour de bon.

Dans ces conditions, si l?artiste n?y est pour rien, si la chose s?est imposée en dépit de sa volonté, les tableaux peuvent tomber du ciel et nul besoin qu?ils transitent par l?atelier.

C?est donc à la présentation de trois aérolithes que nous convie l?exposition chez Emmanuel Hervé.

Entre leur chute et leur livraison, un an et demi s?est écoulé. Car, comme quoi l?exécution a son importance, il faut en général pour Monvert entre un et trois ans entre le commencement d?un tableau et l?achèvement qui permet son souverain abandon. Pour soupeser les météorites mieux vaut les laisser refroidir.

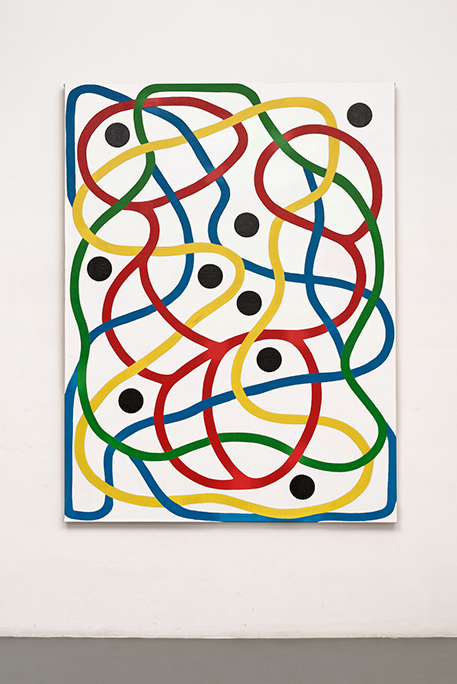

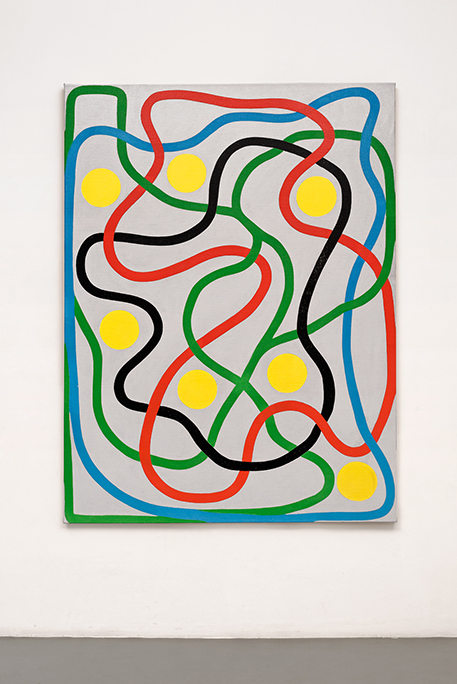

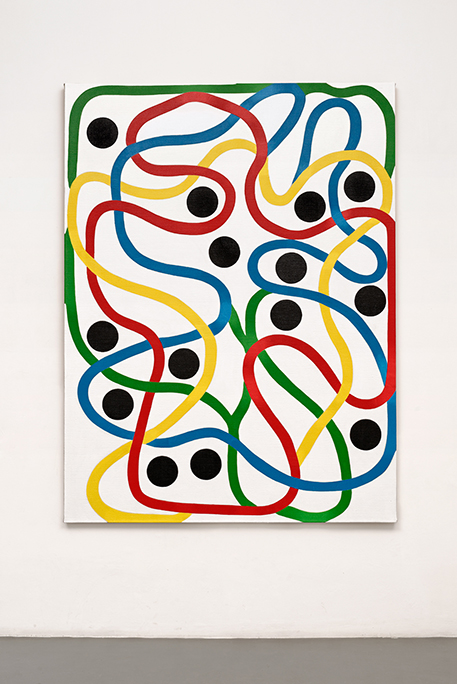

Dans ces trois cailloux, on pourra voir des formes : un c?ur, une tête, un fantôme? Ce n?est pas très gênant avec des cailloux, mais ça l?est un peu plus avec des tableaux censés détachés de tout souci de représentation, des tableaux de 160 x 120 cm, peints à l?acrylique, ce qui est assez inhabituel pour l?artiste, pour qui : « L?acrylique va un peu trop vite. Mais ça s?est passé comme ça ! »

Des tableaux censés ne renvoyer à aucune autre expérience qu?à leur intrinsèque étrangeté. Mais étrangeté à quoi ?

Des tableaux portant des titres en anglais, pour la première fois, l?artiste ne sait pas pourquoi, sinon pour dire que les figures qui s?y sont invitées par inadvertance, Heart, Head et Ghost Writer, sont étrangères à l?abstraction de rigueur, caractérisée par un titre de série en français, lui, mais qui n?engage à rien : Lignes et cercles.

Et au dos des tableaux, des poèmes d?un autre temps, ainsi qu?une précision toujours utile : le nom de la planète d?où ils viennent : « Atelier, Alésia », où selon toute vraisemblance, et malgré tout ce qui précède, ils n?ont pas fait qu?atterrir en octobre 2013.

Frédéric Paul

Pourquoi pas autrement ?

Why not otherwise?

While the Gallery was founded in 2011, Emmanuel Hervé and Charles-Henri Monvert have been sharing 17 years of friendly connivance. And though this may explain many things, it still might seem curious to see the artist?s paintings in the gallery of the young man, thirty years younger.

For Monvert?s second show at the Gallery, three paintings are on display. The gallery would not contain much more, and that?s perfectly fine. So, how were these paintings selected? I asked the artist and the dealer as they were both together that one evening; and as Emmanuel seemed unwilling, or unable to reply, I noticed he was squinting an eye at me while the artist remained silent. So I decided to turn to the latter and asked him directly how and why he had painted these. The answer burst out: ?It came like that. It just dawned on me.? My questions were difficult, and probably somewhat formal, but with an economy of words, the matter was cleared. That is, I wasn?t any further ahead, but I retrospectively understood the quiet supporter?s squint. Mutual understanding can (also) do without words, but then it demands gestures. Since there was no casualness in the artist?s statement, there was no irritation in the second gaze immediately received in return, rather a form of relief, an expression of profound felicity, fully acquiescent at least. Understanding:

_ First: Monvert does not paint. He makes ?tableaux?.

_ Second: a ?tableau? eschews any form of control.

The first assumption is not that absurd after all. Because in order to make a tableau, while it is not forbidden to paint it, it can admittedly also be done otherwise, and in fact, a growing number of artists are striving to keep their hands clean at it. Monvert however actually paints the tableau that he is making, working at it from dawn till dusk. Yet, if he does not insist on the necessary stage of the actual making (to reach elsewhere), or on the studio?s ascetic discipline (where no one is ever invited in, not even his dealer), it is because once the tableau is done ? meaning, once it is considered achieved ? it must dissolve its diligent genesis, if not any traces of it, to offer itself like a phenomenon that would in the end have nothing to deal with whatever preceded here. Not something really novel, but something absolutely new. As if ? fully conforming to the clichés of abstraction ? the field of art was only accessible through an alternative consciousness resulting from some foreign stimulation to the real. This actually comes to be contradicted by the artist?s close circle of friends collecting press clippings, his dealer included, since one of his paintings was acquired by the Fonds national d?art contemporain (FNAC) and is now hanging on the wall of a princely senior administration office, composing the backdrop to interviews given by the successive ministers occupying the position, keeping him company over his back ? an evidence that art can manifest itself even in a ministry?s office, with few distracting occasions left for the guest confronted to an abstract painting; but can anyone claim not to have let the gaze wander during solemn sittings over anodyne details, a pen in its holder, the shade of a radiator, or a speck of mud on the tip of a shoe?

The second assumption is tied to the former, understandably so.

In order for the author of a painting to be plunged into the desired ?cataleptic? state, of the kind that has him claim that there is indeed a tableau before his eyes, that it stands upright, that it functions, like a lamp that lights up when switched on ? and even somewhat better ?, its maker must forget everything dealing with how he got there, technically, but mostly upstream of any technique. What were his intentions when he initiated it, etc? That was indeed the question I had initially asked Monvert, and see where that led us!

Because the artist rules out any notion of project, control, or even of intervention, of any form of protocol to the benefit of a fantastical autonomy of the painting as object, a notion that has been harped on, but rarely in such hilarious way.

Should we mention indiscriminately Knoebel, Molnar or even LeWitt, Monvert remains placid. You must cite Martin Barré to see him thrilled, and Brice Marden to hear him firmly disprove.

The graphite grid that he leaves on the canvas and that remains visible here and there is not a guiding principle; it is like a form of scaffolding that helps composing or escaping a preconceived composition. At any rate, it has nothing to do with the minimalist grid. The scaffolding can remain partly hanging to the work. The American grid is all over. This is what opposes them.

Monvert?s paintings are rather smooth. And yet, according to the artist, everything happens in the pictorial matter rather than in composition or color. The thin layer that grants its consistency to the matter offers the desired (?) tension and chromatic intensity to the tableau. ?Chromatic intensity? being considered as the proper consistency of the painting-phenomena, thus autonomous from the way colors relate to one another. ? Not bad for an abstract painter whose last name combines in French a possessive pronoun and a color with its infinite nuances that even Mondrian refrained from using! Mon-Vert [My-Green] will tell you for example that such strip was yellow, that he could have very well used another color, and that it became black ? which might, or not, be considered a color, my mother was asking me about it recently again, but let?s move on! ?, not because it wasn?t right, not because black is necessarily more satisfying, but because it imposed itself.

As if the order came from above.

As if this injunction to do brought the experience of producing the painting to an antediluvian past.

As if the artist suffered from amnesia, and was even incapable of ?remaking? the painting, meaning unable to retrace its scenario, to reckon its archeology; more destitute in a way than anyone in front of his or her own production, because any other beholder that would be somewhat curious adopts this retrospective process when gazing at a work of interest.

As if ? sorry for the reiteration, Monvert?s confusion must be communicative ?, as if it were not the same painting that was the object of both experiences, execution and scrutinizing, once the former is achieved, once the thread of time is definitely torn.

Under such circumstances, if the artist is not involved, if it was imposed on him in spite of his will, the paintings could fall from the sky and there is no need for them to pass via the studio.

The show at Galerie Emmanuel Hervé thus invites us to consider three aerolites.

A year and half passed between their fall and their delivery. Indeed, execution is important, Monvert generally needs anywhere between one to three years from the initiation of a painting to its achievement allowing for its sovereign abandon. To feel the weight of meteorites it is better to let them cool down.

Forms may be discerned in these three stones: heart, head, ghost? While this may not be too disturbing when dealing with stones, it becomes more so with paintings meant to be detached from any representational intention, frames of 160 by 120 cm painted with acrylic, which is rather unusual for the artist who considers that ?Acrylic is a little too fast. But that?s how it happened!?

Paintings meant to lead us to no other experience than that of their inherent strangeness. Yet, strangeness to what?

Paintings with English titles ? for the first time, and the artist can?t explain why other than by claiming that the figures that invited themselves inadvertently, Heart, Head and Ghost Writer, are foreign to the usual abstraction, while the series holds a noncommittal French title: Lignes et cercles [Lines and Circles].

And at the back of the paintings, poems from yester years, and a useful detail: the name of their original planet: ?Atelier, Alésia? [Studio, Alésia], where it is likely, despite what precedes, that they did much more than just land in October 2013.

Frédéric Paul

translated from the French by Frédérique Destribats