Presentation :

ordem desunida

Tiago Mesquita

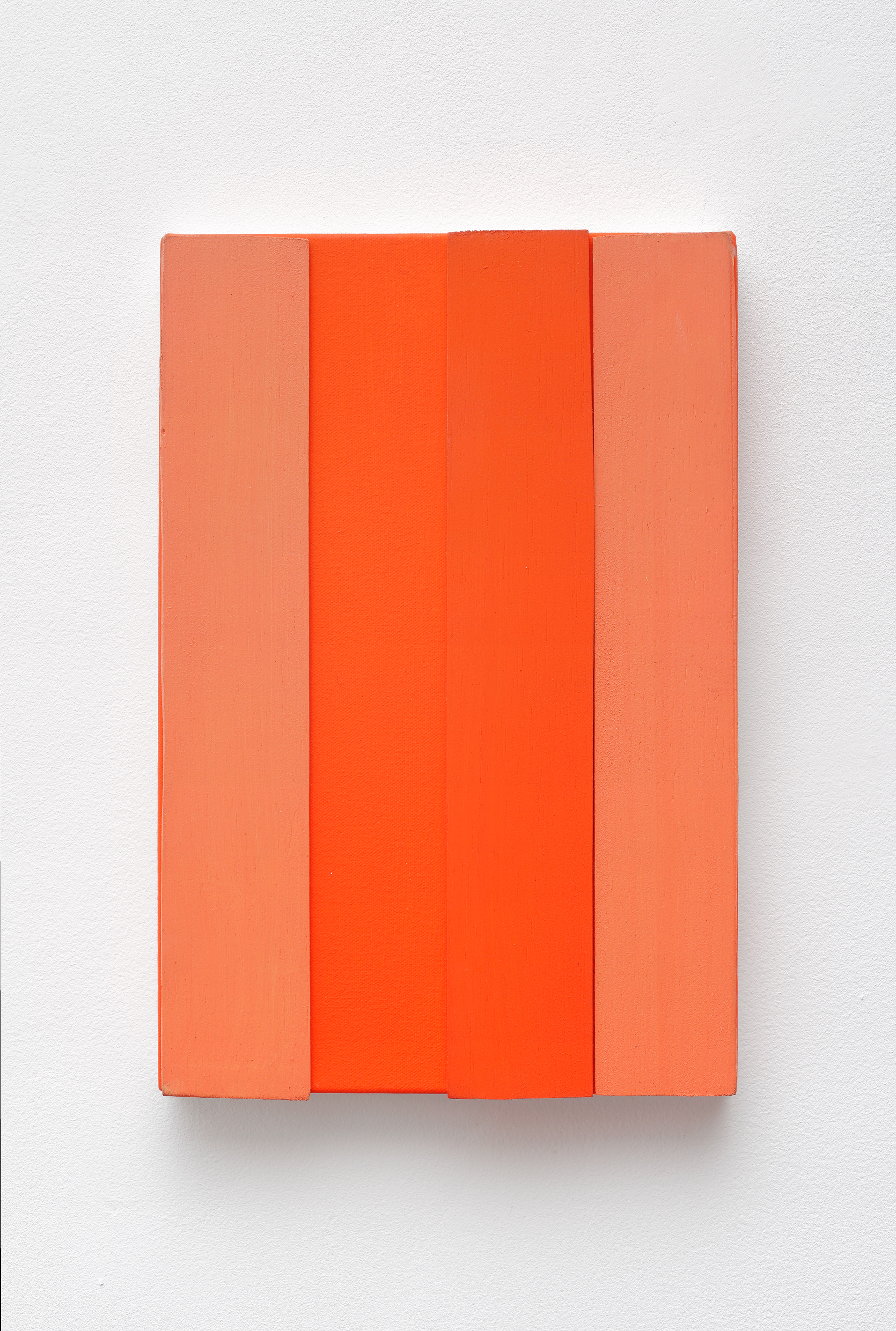

Sérgio Sister is an artist from the field of color. His painting shapes abstract spaces by associating layers of paint and brushstrokes on a plane. The artist renders a combination of similar colors heterogeneous and varied. Thus, a monochromatic plane – like many in this show – can display numerous variations. He is not interested in the immediate perception of the difference between things. The contrast takes place between similar elements. It appears in a meditative way. It makes us see what was monotone as variegated. This is achieved in a subtle way. Sister paints delicate passages of hue and light.

Seldom does the artist use stark contrasts, or pure colors straight out of the tube. The colors seem to transform, to take on luminous differentiations. He uses wax to lend heterogeneous features to a scarcely varied color palette. Mixed with the paint, it evinces the brushstroke marks, rendering the painting’s material more solid and opaque. Oftentimes, the color also comes mixed with metallic pigments.

They give the plane a slightly flickering appearance, emphasizing the different directions that the brush moved in. Thus, in Ordem desunida (Disunited order), even the ordinary colors, the regular oranges, the vibrant yellows take on the complexity of colors that have no name.

In these near-monochromes from the recent show, brushstrokes move in different, oft-divergent directions. We take the surface both as a plane of continuous colors and as an accumulation of small, disarticulate optical phenomena. It is both things. One continuous color that frays out and myriad elements coming together in a more or less troubled way. Although the color maintains unity, the plane grows in complexity – it could be a mosaic, with shards looking for some degree of unity. This is not so, however, for here we see less of a synthetic imageand more of the fractures.

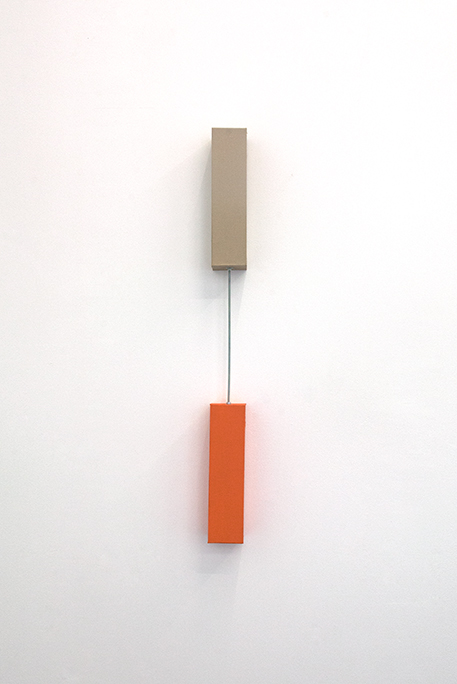

It had been a long time since paintings had played such an important role in a Sérgio Sister exhibit as they do in Ordem desunida. Lately, some of his efforts turned to creating 3D works and reliefs that carry the questions from his painting into regular space.

These efforts bred series like Ripas, Traves, Pontaletes, Caixas and Tijolos. Very dissimilar among themselves, these object-like pieces are featured in the show, but this time the paintings seem to be what’s new. Their new features are emphasized by the fact that these works are shown side by side with the objects. We see similar color relationships, and above all a less frontal interlocution with the object. What happens on the sides of the paintings is as important as in the 3D pieces.

However, what catches the eye the most is the use these paintings make of intervals. This was learned with the sculptures and objects. In the ripas (wooden slats) and caixas (boxes), the junction of one plank with another is interrupted by a fissure, a fracture, an interval. Something appears to take place between one stretch of color and the other that renders the relationship between these elements more indeterminate.

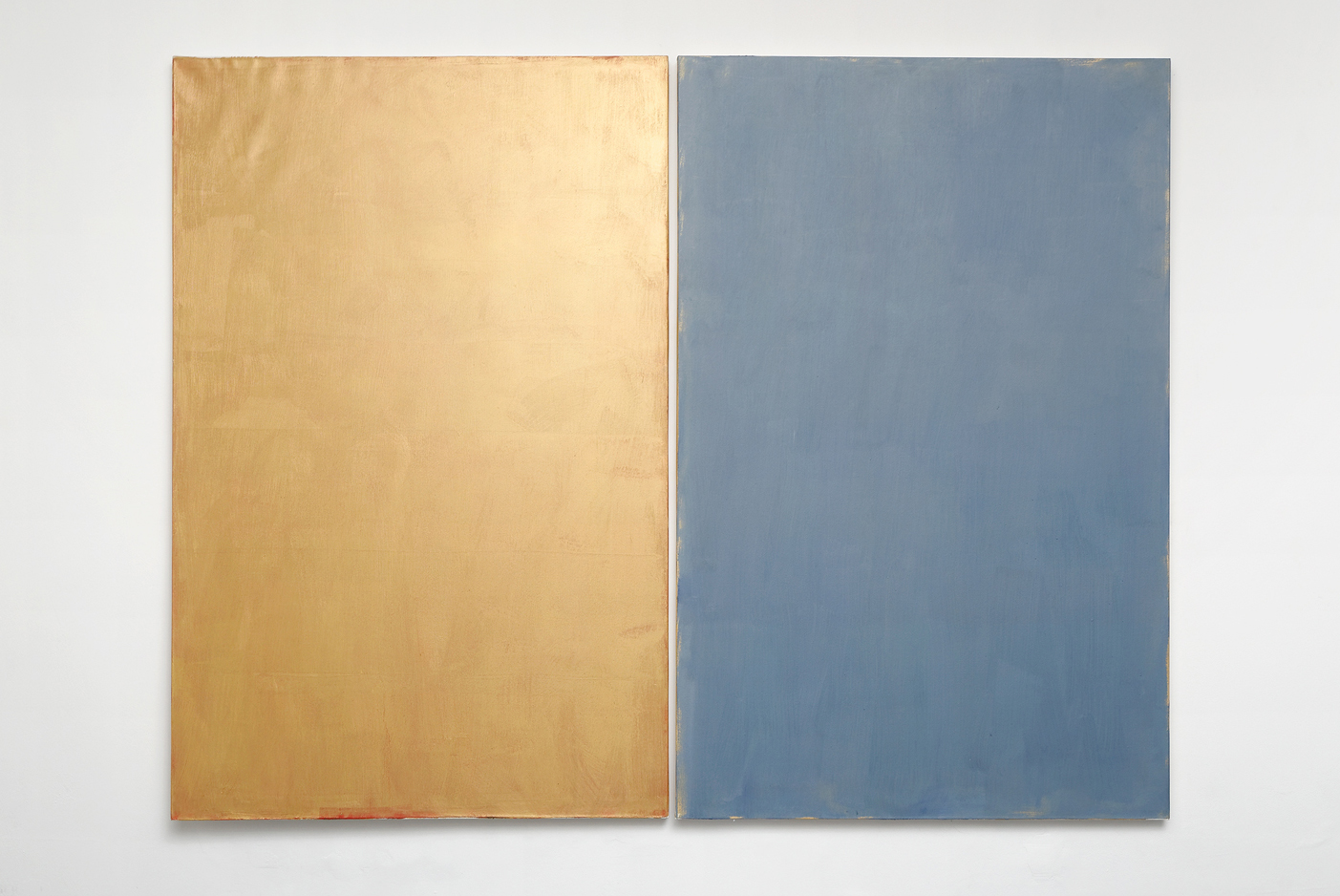

In this show, the artist presents three new groups of paintings. They are series of pieces where a handful of procedures repeat themselves. There are small, near-monochrome pictures, large diptychs with two dominant colors, and thin, tiny pictures covered with narrow vertical wooden slats. Although they are very different from each other, this idea of interval, taken from the 3D work, is important in all of them.

The surface is never completely covered by the primary element in the painting. In the small, near-monochrome pictures, the dominant layer of paint does not run the whole length of the canvas.

We see other layers, other forms of painting working behind the foreground. In the pictures with wooden slats, what was supposed to cover the surface also leaves gaps, allowing us a glimpse of other forms of painting. The number of elements grows and the order that might have been attributed to the picture grows more complex.

In the diptychs, this relationship is even more evident. They are two large canvases almost entirely covered with one color. In one of them, for example, a predominantly green canvas is placed three centimeters away from an almost completely silver-colored one. The field of each color is built through gestural, repetitive, rhythmic brushstrokes. The brushstroke marks are very different in each of the pictures. The colors are very different. Some are elaborate, created through original pigment combinations, while others are vulgar, with colors which, despite having been altered, are associated with the vulgar palette of industry and the kitsch side of art production.

Underneath the paint that dominates the surface, the color from the neighboring picture appears. As if one color had gone from one side to the other. One color might be expanding while the other contracts, and the opposite could also be true, or both could be receding, losing their vigor. In fact, it doesn’t really matter. What’s important here is that the dynamics of Sister’s paintings, which were already detail-rich, for instance, since his monochromes from the eighties and nineties, have incorporated new variables. Thus, we see colors on the edges that aren’t the dominant color from the monochrome on the right or on the left. The sight of the boundaries of colors, of what shows underneath, is as important as the way the color behaves upon the surface. The artworks seem to articulate events that were interrupted, split up, articulated in a complex way. The painting forms a unit of disarticulate phenomena, just like in Degas and Seurat. Thus, the lilac smudge that appears on the edge of the canvas seems as important as the greenish tone that runs the length of the surface. Everything seems to have weight in this painting.

In a brilliant way, Sérgio Sister suggests a less hostile relationship with the gaze. Nothing is identifiable at once. Relationships prove more complicated. The artist looks for a way for delicate materials to coexist in a civil manner, despite irreconcilable differences. He does so without pacifying them, without homogenizing them. Considering the harsh social climate in Brazil and the world, where rationality is lacking, maybe this is all that’s needed.