Presentation :

Movie kisses keep coming on a laptop desktop. Each newly opened window shows one of those archetypal sequences that sum up the Hollywood love story. From one extract to another, the continuous effect of the travelling emphasizes the intertwined bodies' movement. Those scenes (all of them found on YouTube or Dailymotion websites) have been shot again by Pierre Paulin and the film was then blown up on 16mm stock.

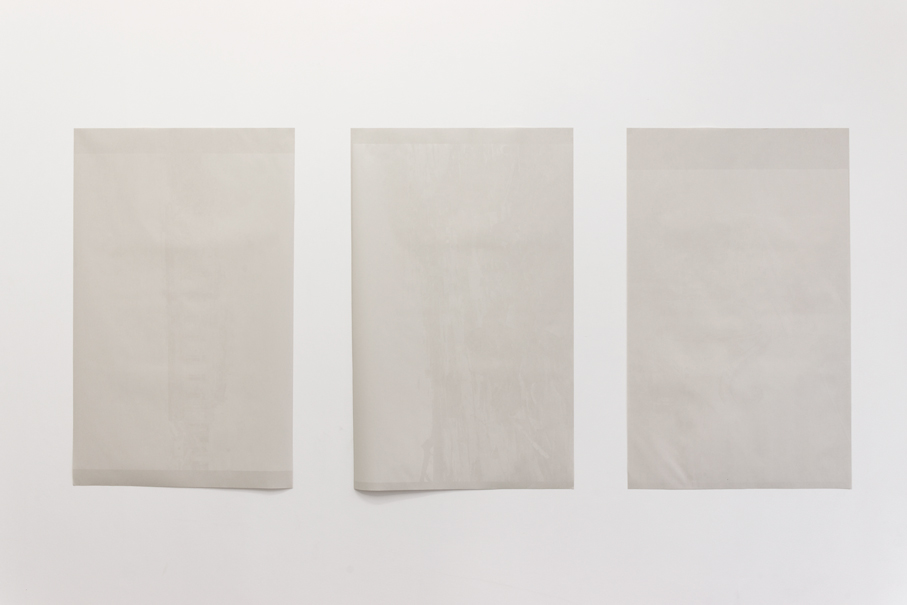

Next to this film, on another wall, images were printed in white on white and are slowly revealing themselves as the paper yellows throughout the exhibition duration. L'industrie refoulée is lying on the floor: a few words were engraved on rotogravure cylinders. At the opposite of what those brief descriptions of Paulin's works imply, the artist claims he doesn't address any nostalgia for these out-of-date (or soon to be) technologies: Paulin was born after the rise of 16mm amateur cinema and is merely witnessing its current decay. However, the artist shows no hesitation in using this technique or to evoke rotogravure via its fragile and bulky cylinders, whose storage difficulties are among the crucial issues that jeopardise its profitability and durability. Seen through the contemporary art lens, the obsolescence of certain technologies is rapidly becoming meaningless. Technology that no longer belong to our world obviously persist in contemporary art practices, while barely created or uploaded digital pictures instantly disappear in the flood of old images constantly substituted by new ones.

The film described above, made of found footage Hollywood kisses, is named Vertigo. It evokes both the dizziness created by the accumulation of images and Alfred Hitchcock's eponymous film. Paulin contextualizes his works and places them at the precise (although fictional and virtual) junction where two cultural and technical eras may connect ? hence revealing two ways to use movies and fictions. The artist plays with this space-time - either incompressible or larger than life - where a technological change happens. It is also within this interval that, during the time of an artwork, two different modes of representation superimpose: the collective cultural memory on the one hand, and the personal, emotional ? almost intimate ? considerations that come with it on the other hand.

Paulin explores the similar uses of the Internet and techniques that pre-existed: the cinema and other means of mechanical reproduction (e.g. rotogravure, offset printing, etc.). He plays with the habits and attitude one develops with new technologies and which are often instinctively passed from one generation to another. In this regard, he says: "For example, from the internet interactive interface to the movies, I consider web browsing as a form of editing." Thus, the artist observes the evolution of our relationship to images and texts as infinitely reproducible and mass produced data, up to the point where their contents may not matter to him.

Such an approach might be perceived as being slightly romantic, especially considering the fact that Paulin adds further autobiographical elements to it. But the use of common technical forms and materials reject such interpretation. His practice includes the desktop ? the computer one ? as a standard tool in which the private and the public spheres inevitably intertwine. In his own words: "If I chose to mix images found on the Internet with those of the person with whom I share my life, it's just that they found themselves being next to each other on my computer screen. Personal life is constantly mixed with public information. This should not be considered as a gesture, but as a condition of the tool with which I work. The computer or the Internet interest me mainly as standard format or medium."

Caroline Soyez-Petithomme

----------------------------

Des baisers de cinéma s'enchaînent sur le bureau d'un ordinateur. À chaque fenêtre qui s'ouvre, une de ces séquences archétypales de la passion amoureuse hollywoodienne commence. Le travelling qui accompagne l'enlacement des corps se prolonge d'un extrait à l'autre. Ces scènes (toutes trouvées sur les sites Youtube ou Dailymotion) ont été de nouveau filmées par Pierre Paulin directement sur l'écran d'ordinateur, et le film a ensuite été gonflé en 16mm.

À côté de cette projection, sur un autre mur, des images imprimées en blanc sur blanc se révèlent au fil de l'exposition grâce au jaunissement du papier. Au sol gît L'industrie refoulée : quelques mots et textes gravés sur des cylindres de rotogravure. Contrairement à ce que les descriptions succinctes de ses oeuvres induisent, l'artiste affirme qu'il ne cherche nullement à exprimer un sentiment de nostalgie face à des technologies désuètes ou en passe de le devenir. Il est de fait bien trop jeune pour avoir par exemple connu le développement du cinéma amateur 16mm. Bien qu'il ne soit contemporain que de son obsolescence, Paulin ne se prive pas d'utiliser cette technique. Il en est de même lorsqu'il évoque la rotogravure via ses cylindres, encombrants et fragiles, dont le stockage est l'un des problèmes majeurs qui menace sa rentabilité et donc sa pérennité. Replacée dans le champ de l'art contemporain, la désuétude de certaines techniques devient rapidement caduque. Force est de constater que les technologies n'appartenant plus à notre quotidien persistent dans les pratiques artistiques contemporaines et qu'en contrepoint, l'image numérique, à peine créée ou mise en ligne, s'épuise et disparaît comme si les flots de nouvelles images se substituaient sans cesse aux précédents.

Vertigo, ce found footage de baisers de cinéma précédemment décrit, évoque cet effet de vertige lié à l'accumulation des images, mais aussi le film éponyme d'Alfred Hitchcock. Paulin contextualise ainsi ses oeuvres et les place à la jonction précise (bien que fictive et virtuelle) où se rejoindraient deux ères techniques et culturelles, mais aussi deux façons de consommer le cinéma et la fiction. L'artiste rejoue cet espace-temps - incompressible ou trop étendu à l'échelle d'une vie humaine - où survient un changement technologique. C'est aussi dans cet intervalle que se superposent, le temps d'une oeuvre seulement, deux modes d'écriture de la mémoire culturelle collective et des projections personnelles, émotionnelles voire intimes qui l'accompagnent.

Paulin explore les usages analogues que nous faisons d'Internet et des techniques qui ont existé avant lui : le cinéma et d'autres moyens de reproduction mécanique (rotogravure, impression offset, etc.). Il s'amuse des habitudes pratiques ou des réflexes technologiques que nous développons et qui se sont transmis de façon parfois instinctive d'une génération et d'une technique à l'autre. À ce propos, il explique : « par exemple, entre l'interface interactive d'Internet et le cinéma, je considère la navigation sur le Web comme une forme de montage. » Il observe ainsi l'évolution de nos relations à l'image et au texte comme données reproductibles à l'infini et produites en masse, à tel point que leur contenu lui importe parfois peu.

Une telle démarche n'est peut-être pas dénuée d'un certain romantisme, Paulin y ajoutant également des éléments autobiographiques. Mais l'utilisation de formes et de supports techniques communs vient réfuter cette interprétation. Sa pratique intègre simplement le bureau, celui de l'ordinateur, comme un outil standard où le privé et le public s'entremêlent inévitablement. À ce sujet, il précise: « si j'ai choisi de mélanger des images trouvées sur Internet avec celles de la personne avec qui je partage ma vie, c'est simplement qu'elles se sont retrouvées en même temps sur l'écran de mon ordinateur. La vie personnelle est constamment mélangée à de l'information publique. Ceci ne doit pas être considéré comme un geste, mais comme une condition de l'outil avec lequel je travaille. L'ordinateur ou Internet m'intéressent essentiellement en tant que format ou médium standard. »

Caroline Soyez-Petithomme