Presentation :

Camila OLIVEIRA FAIRCLOUGH was born 1979 in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) ? Lives and works in Paris (France)

« MMM ...MM ...K ...H » par Lætitia Paviani, 2013

Chris m'avait installé de telle sorte qu'elle puisse se coucher sur moi, sa tête relevée, avec ma main sur son visage (...) Puis elle m'a indiqué, en levant mon doigt, et en le laissant retomber de manière répétitive sur son oeil, qu'elle souhaitait que je donne des légers coups sur sa paupière. Lorsque je l'ai fait de ma propre initiative, elle a d'abord souri, puis elle a ri (...) Pendant ce temps elle léchait et reniflait la paume de ma main, et murmurait quelque chose qui pouvait ressembler à une mélodie. Nous avons fait cela pendant quinze à vingt minutes.

Le monde sans les mots. Comment l'identité sociale des enfants sourds et aveugles est-elle construite ?

David Goode, éd. Érès 2003

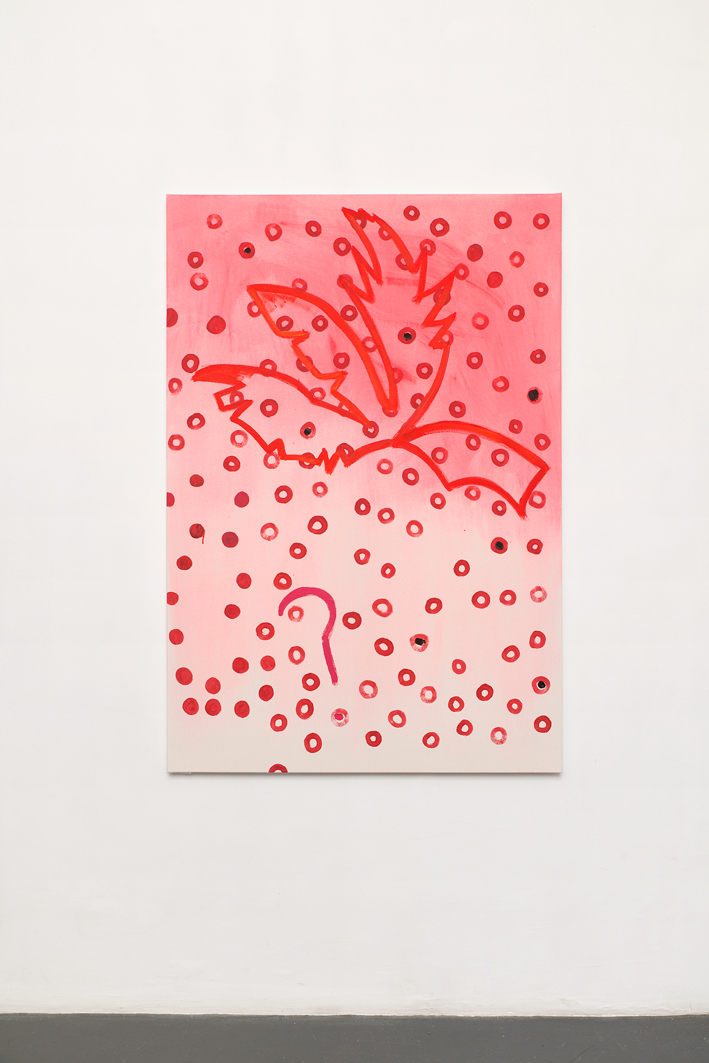

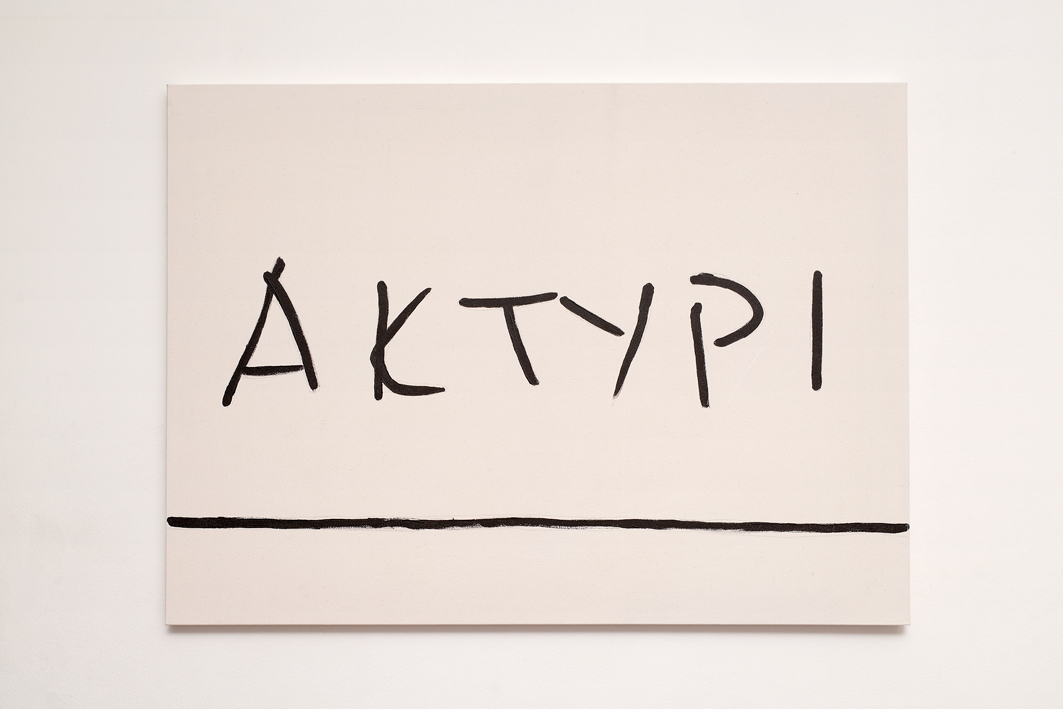

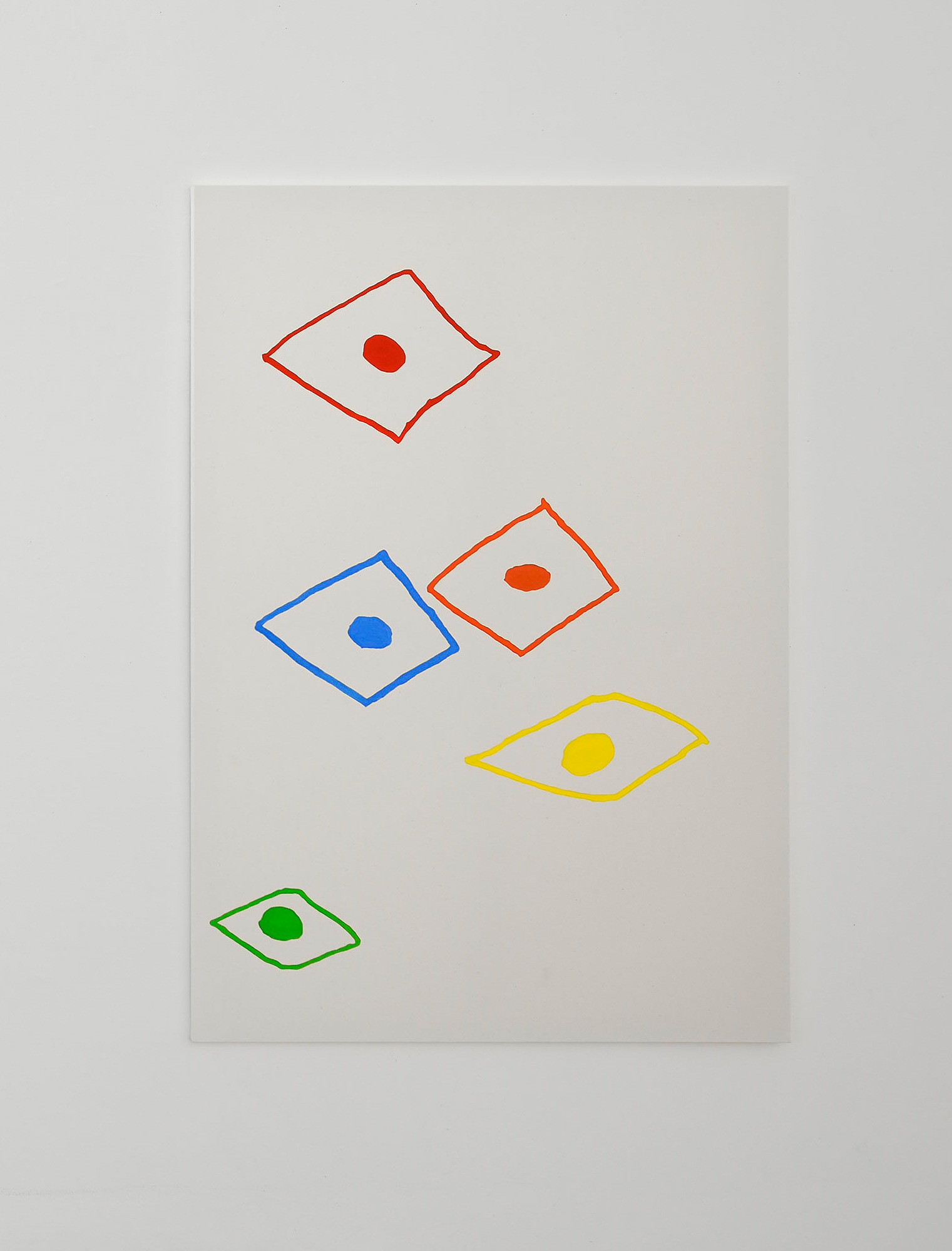

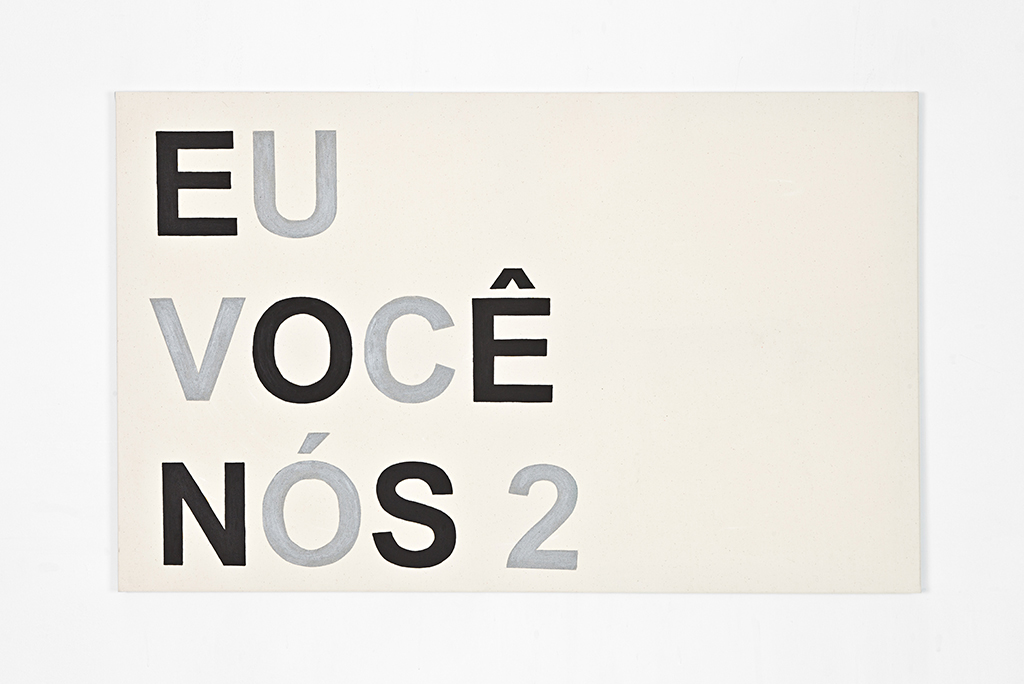

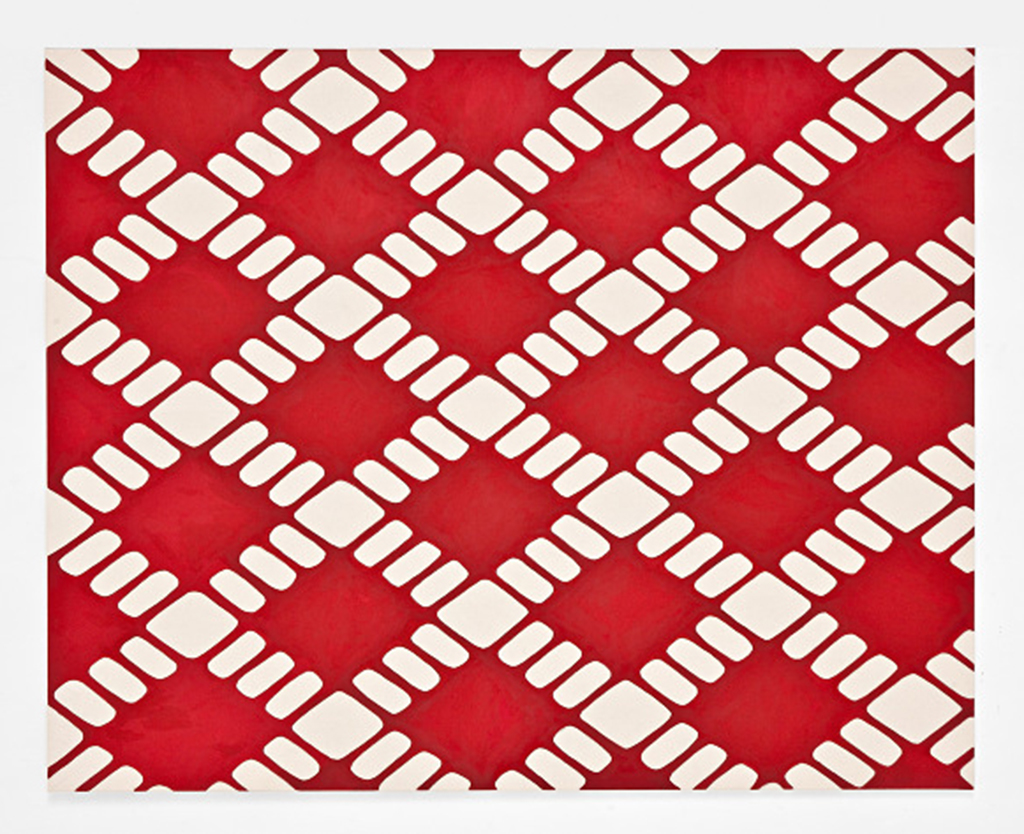

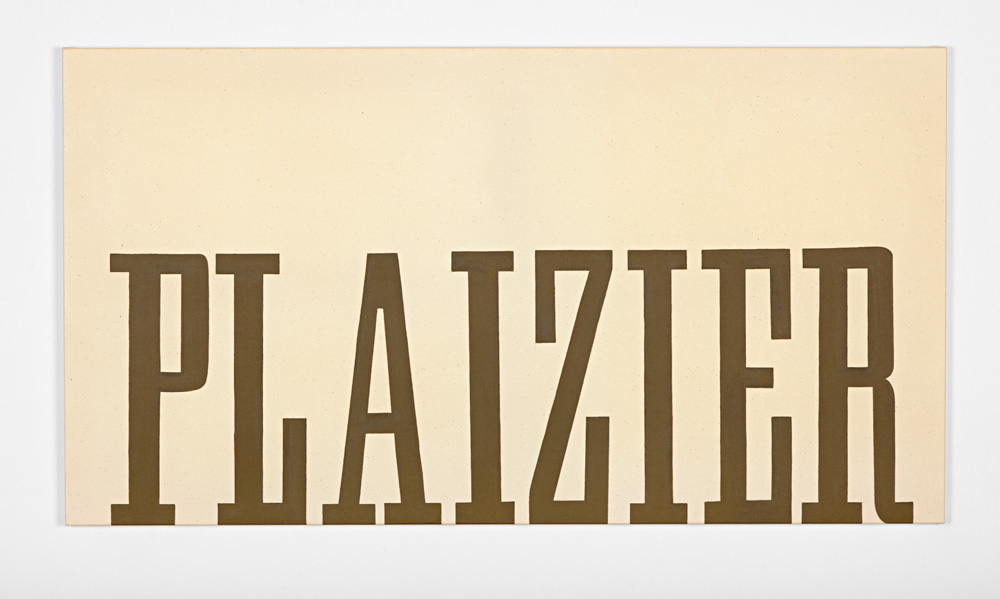

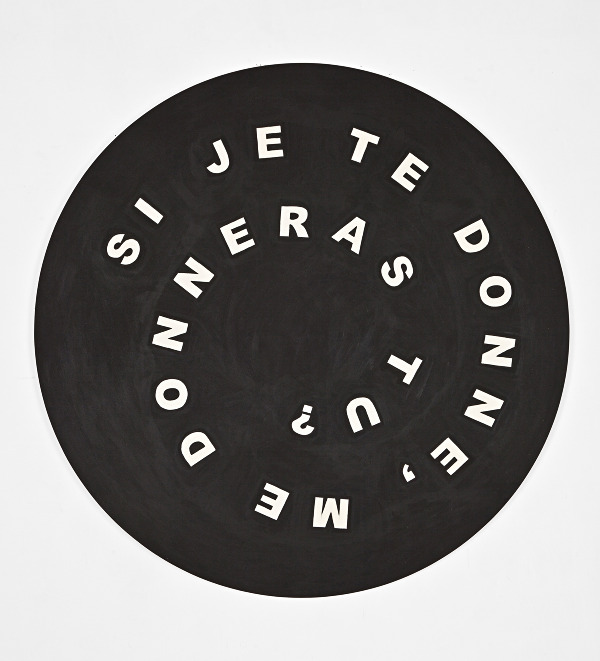

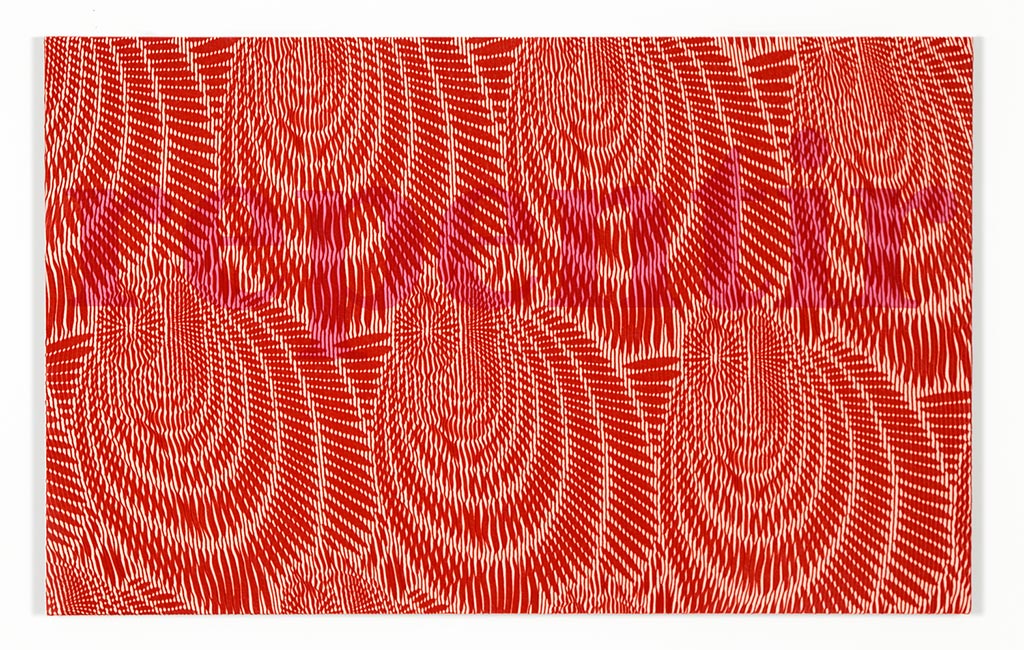

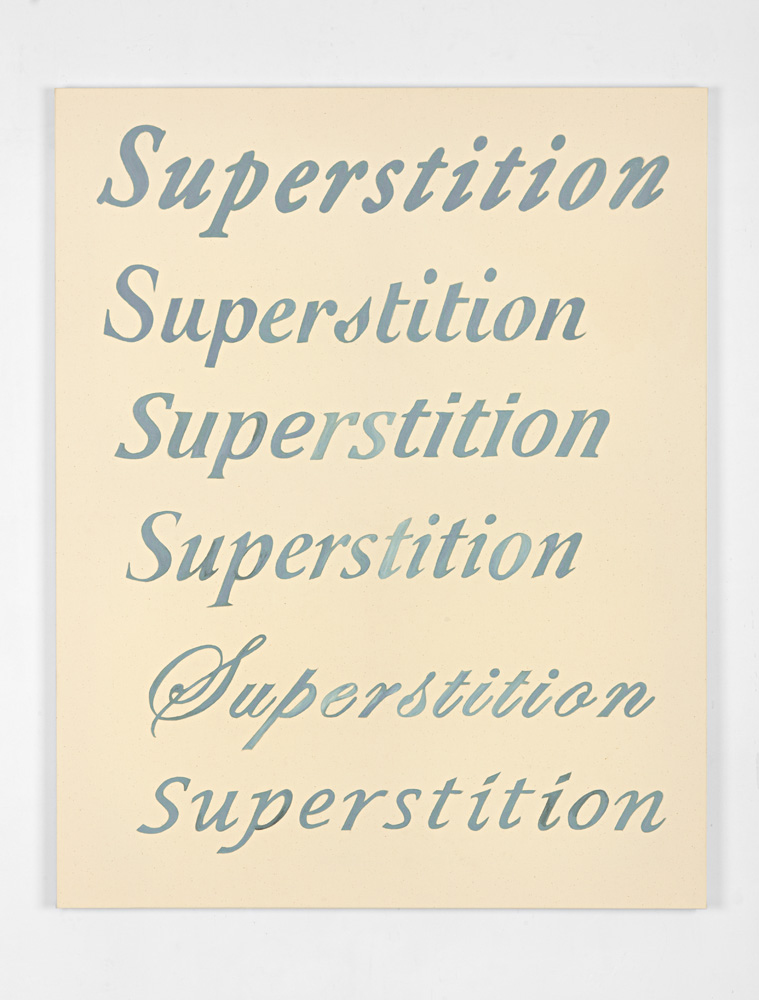

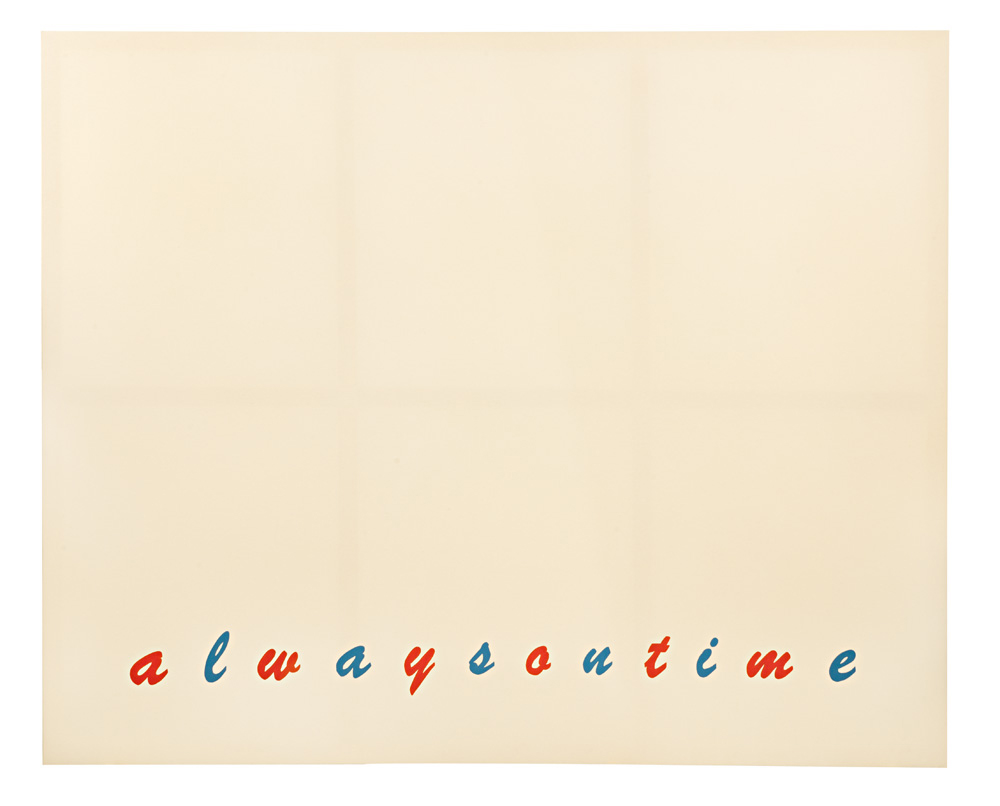

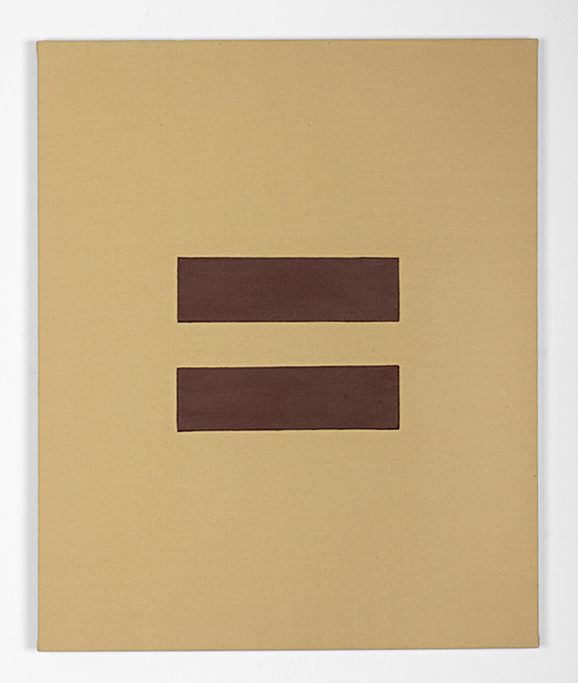

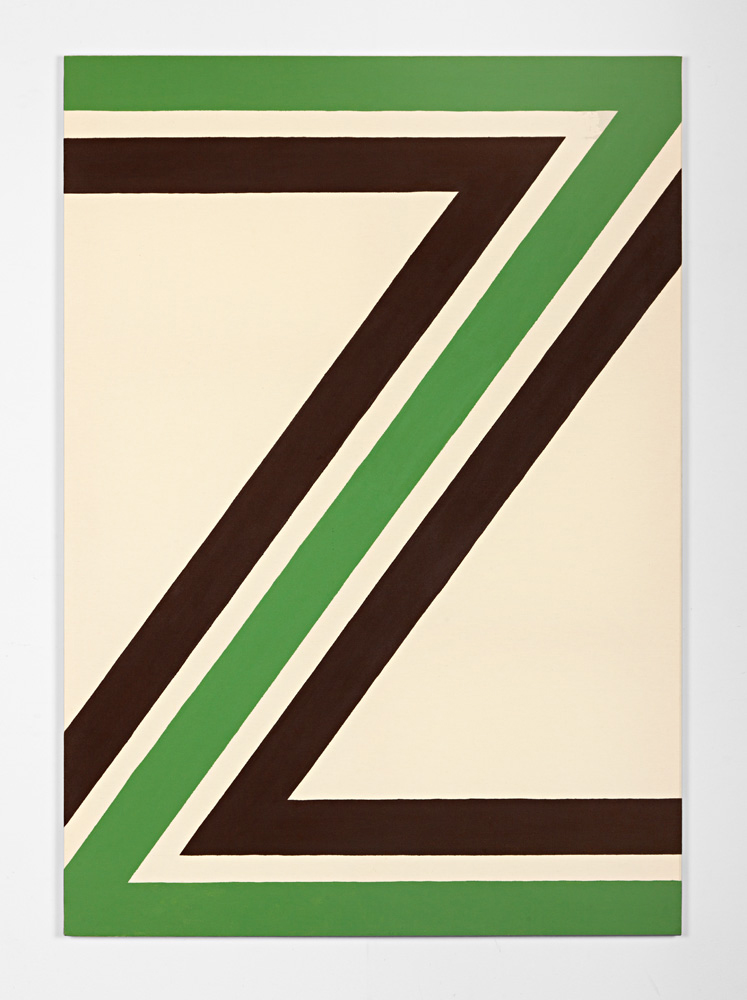

Comment dire. Peinture. Langage. Deux thèmes trop vastes pour être discutés ici. Pourtant c'est ce que dit très simplement chaque mot peint sur chaque toile de Camila Oliveira Fairclough, chaque abstraction colorée et symbolique, chaque mécanique corporelle codée, l'inscription très nette de l'artiste dans le champ des avant-garde et dans celui de son propre multiculturalisme. Cependant les mots de Camila ne cherchent pas à fabriquer la moindre représentation commune du monde, ils ne sont pas là pour ça. « Sensationnel, chers auditeurs, les mots me manquent ! » lâche l'un des enfants aveugles du documentaire de Johan van der Keuken, embarqué sur une grande roue avec un enregistreur radio. Il faut voir les choses ainsi, c'est-à-dire autrement, voir pas du tout. C'est ce qu'éprouve David Goode, ce chercheur et enseignant pré-cité, lorsqu'il décide de modifier son interaction avec Chris, sourde, muette et aveugle, pour tenter une improbable communication : il lui laisse organiser leurs activités communes, en restant passif et obéissant. Il désigne alors cette nouvelle activité par les sons produits par l'enfant pour se souvenir que son objectif était de se débarrasser de son propre « babillage ». À mon tour d'opérer une inversion : Malgré l'omniprésence de tous ces mots, il faut que j'oublie leur réalité, il faut que j'en fasse abstraction (ce que fait l'artiste). Hors de toute symbolique du langage et hors de leur usage courant, ces mots tout comme les objets que Chris manipule à sa façon, sont les motifs d'expériences réjouissantes et variées. Si maintenant, je considére tous ces mots, comme autant de Chris et de David Goode (Camila donne des noms à ses tableaux plutôt que des titres), j'observe la naissance d'une possible expression codée entre eux et moi, fondée sur des projets communs (la peinture par exemple mais aussi la performance) à partir d'une réserve de savoir pratique disponible (ce que Camila nomme « déjà vu » pour parler des sources visuelles diverses qu'elle collecte). Alors enfin je peux me saisir d'une notion évoquée par Merleau-Ponty dans sa Phénoménologie de la perception, et en contemplant les ?uvres de Camila, envisager chacune de ces consciences éveillées et présente au monde, non pas comme des « je pense que » (je parle) mais comme des « je peux ».

« MMM ...MM ...K ...H » by Lætitia Paviani, 2013

Chris had settled me so that she could lay on me, her heand raised with my hand on her face (...) Then she showed me, by raising my finger and allowing it to fall again repeatedly on her eye, that she wanted me to tap her eyelid gently. When I di dit on my own initiative, she first smiled, then she laughed (...) At the same time she was licking and sniffing the palm of my hand an murmured something that could resemble a tune. We did this for fifteen to twenty minutes.

The world without words. How is social the indentity of blind and deaf children constructed ?

David Goode, pup. Érès, 2003.

How do you say. Painting. Language. Two themes that too vast to be discussed here. However it is what each word says very simply painted on each canvas by Camila Oliveira Fairclough, each coloured and symbolic abstraction, each coded corporeal mechanic, the very clear inscription on the artist in the field of the avant-garde and in that of his own multiculturalism. However, the word of Camila do not try to fabricate the last common representation of the world, they are not there for that.

« Sensational, dear listeners, words fail me ! » lets out one of the blind children in Johan van der Keuken's documentary, on board a big wheel with a radio recorder. You have to see things in this way, in other ways, otherwise, or not at all. This is what David Goode feels, the researcher and the teacher mentioned earlier, when he decides to change his interaction with Chris, deaf, mute and blind, to try improbable communication : he lets Chris organize their common activities by remaining passive and obedient. He names this new activity by the sounds produced by the child « MMM ...MM ...K ...H » to remember that his aim was to get rid of his own « babbling ». It was my turn to make a reversal : despite the omnipresence of all these words, I need to forget their reality. I have to disregard them (what the artist does). Beyond all symbolic of language and beyond their normal usage, the words, like the objets that Chris handles in his way, are motifs of gratifying and varied experiences. If not I consider all these words as being as much from Chris as from David Good (Camila gives names to her paintings rather than titles), I Observe the birth of a possible codiified expression betwen them and me, founded on common projects (painting for exemple, but also performance) from a reserve of available practical knowledge (what Camila names as « déjà vu » to speak of varied visual sources that she collects). So finally I can grasp a notion mentioned by Merleau-Ponty in his Phenomenology of Perception, and in contemplating the word of camila, to consider each of these awakened consciences, present in the world, not like « I think that » (I speak) but as « I can ».